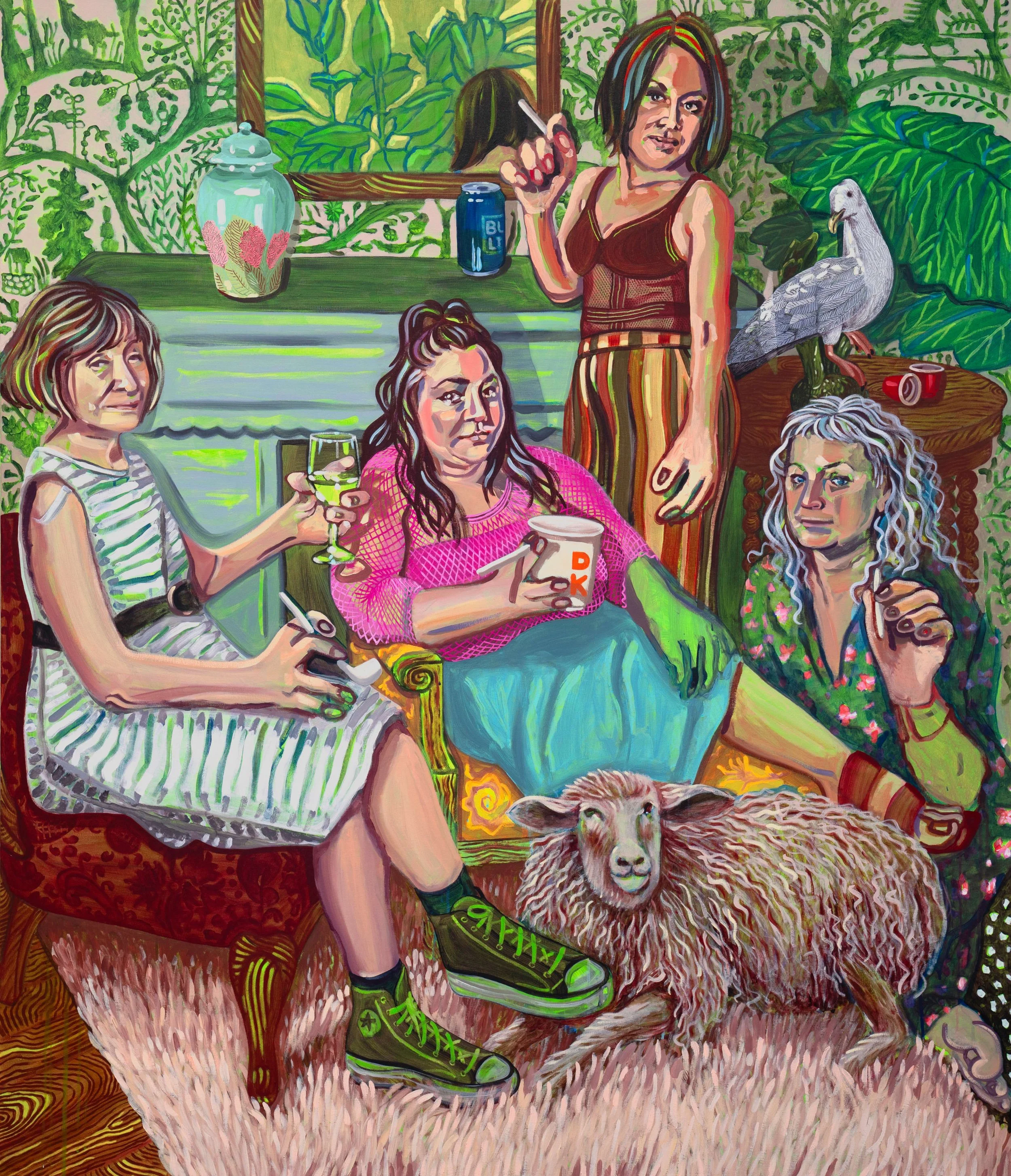

Isabella’s Seagull, Ishikura, 2024, Acrylic and Oil on Canvas, 70 x 60 x 1.5 in

new visionary magazine

Artist Feature: Barbara Ishikura

May 28, 2025

What initially drew you to using portraiture as a vehicle to investigate identity?

Before turning to portraiture, I was making abstract collage work, but I found myself increasingly frustrated by the limitations of abstraction in conveying personal narrative. I knew I wanted to tell a story — specifically about my own life and the complex, often contradictory experience of living in a female body. That desire led me to begin painting women. Once I did, I realized that women painting women is still relatively radical in the history of art. Portraiture gave me a way to claim agency over female representation and to explore identity with specificity and nuance. Evey time I paint another woman, I’m also painting aspects of myself — my memories, tensions, joys, and cultural experience. There’s an emotional recognition of shared experiences between my subjects and me. Portraiture allows me to build those connections while examining broader themes of femininity, class, and social performance through the lens of the body.

The Curator, Ishikura, 2024, Acrylic and Oil on Canvas, 60 x 60 x 1.5 in

You mention that your work juxtaposes classical art historical atchetypes with working-class iconography. How do you see this contrast playing out in the broader cultural conversation about class and sophistication?

I’m fascinated by the cultural assumptions around taste — what’s considered “good” or “bad” — and how those hierarchies are literally man-made. In my work, I deliberately juxtapose classical art historical archetypes with working-class iconography to question these constructed notions of sophistication. For example, I often paint women holding Dunkin’ Donuts coffee or drinking cheap beer instead of more “refined” artisanal choices. These small, familiar details carry weight — they signal class, background, and social positioning. I’m especially interested in the moment when someone “knows better” but still chooses something deemed lowbrow. What does that say about identity, rebellion, or authenticity? Having grown up in a working-class household and now finding myself in a multicultural and privileged spaces, I’m intimately aware of how both worlds express themselves aesthetically — and how often those expressions clash. My paintings reflect that tension and challenge viewers to reconsider the arbitrary value we place on cultural markers like food, clothing, décor, and behavior.

In your artist statement, you mention challenging the cultural hierarchies that dictate aesthetic preferences. How do you approach this in your visual discourse, and what strategies do you use to confront these social and cultural expectations in your work?

In my work, I intentionally use contrasting painting techniques to challenge aesthetic hierarchies. Paint application plays a central role — I’m drawn to the tension between refined, formally accurate passages and more clumsy, even grotesque ones. For example, I often render faces with great care, using tone, glazing, and anatomical precision. In contrast, a hand in the same painting might by sketchy, exaggerated, almost monstrous. I’ll sometimes mix in a heavy medium to make certain objects appear awkward or unrefined, disrupting the illusion of something polished. My palette also reflects this dialogue. Though people often describe my paintings as bright, I actually use a lot of browns and grays, which allow the few vivid colors to visually pop. These choices are deeply personal. The dark subtle tones connect to my time immersed in Japanese culture and aesthetics, while the bolder colors remind me of the working-class American world I come from. I’m fascinated by these visual contradictions because they echo the contrasts I navigate in my daily life.

Felicia by the Pond, Ishikura, 2023, Acrylic on Canvas, 48 x 60 x 2.5 in

How does your role as an educator inform your artistic practice, and what lessons or insights do you aim to pass along to your students?

Teaching at MassArt keeps my eye sharp, especially when it comes to the figure. I teach a lot of figure drawing, and it reminds me of my own undergraduate experience, where drawing from the figure every day built a deep foundation. I know that’s less common now, so I try to give my students that kind of immersive practice. At the same time, I also want to show them that drawing and painting can be expansive — it doesn’t have to be confined to a flat surface. Recently, I started building objects from my paintings in papier-mâché, and then painting them with oil paint as I would on canvas. This process has opened up new ways of working, and I’ve brought that into the classroom. For their final project, my students are creating large papier-mâché objects and drawing directly onto them. I want to give them — and myself — permission to move freely between materials, to explore, and to see drawing as a living, flexible language.

What role does manifestation play in your life and creative work, and do you have a go-to ritual or method that helps you call in what you’re seeking?

For me, manifestation is about expressing my truth through visual language. Painting and drawing are the ways I make sense of my life, my experiences, and the world around me. Visual language is the most powerful tool I have for communicating what I feel and observe — it’s where I find clarity. My understanding of the world “manifests” in the making of the painting itself. When I begin a painting, I have a sense of who the model is, since I work from photos, but the environment unfolds more organically. As I paint, an image will often emerge — like a donut with a giant bite taken out of it or a dog pissing on a birdbath — and it just feels right, so I lean into it. Often, when I paint the model’s face, I feel emotionally connected to that person. Other times, the imagery of objects feels humorous to me, and I love that contrast.